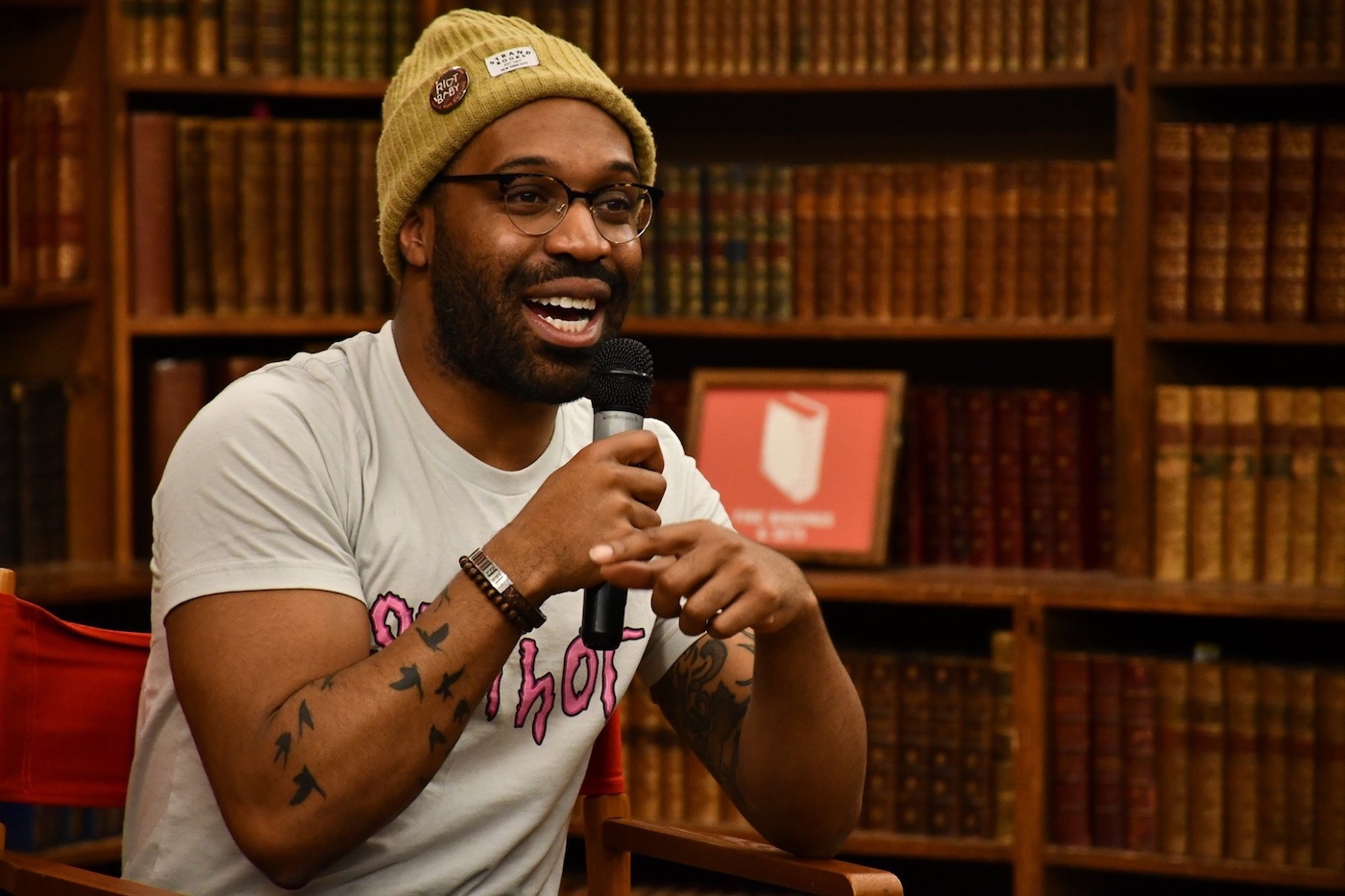

There’s a sense of heightened reality that occurs when you see Marlon James (author of the rich fantasy Black Leopard, Red Wolf) and Tochi Onyebuchi (author of the not-actually-dystopic superhero tale Riot Baby) sitting on a public stage, before a rapt crowd, speaking with each other. Either of them alone exhibits superhuman charm, but put the two of them together and they become a Super Saiyan of wit. A veritable Voltron of expertly-deployed shade. A drift compatible charisma Jaeger, if you will—except one half of the Jaeger’s wearing a shirt that says “Slipthot” on it, and the other half is super into Can.

And lucky us, they got together for an event at the Strand! The two authors discussed writing, anime, and life in a violently white society, the X-Men, Sarah McLachlan?, and American Dirt, amongst a mosaic of topics. We’ve provided a transcript below.

Marlon James: So we’re gonna talk about Riot Baby, we’re gonna talk about writing […] You know, the first thing I thought—because it’s almost the reverse of what I’m doing. I wrote this other kind of very contemporary novel, which is really insulting when people call it historical—I’m like, I lived through it, it’s not historical—and I moved to a fantasy kind of story. A lot of people look at this as a sort of a change in gears. Does it feel that way to you?

Tochi Onyebuchi: I think the way in which it feels like a change is that it’s the first published adult work that I have. At the same time, when I was growing up, I wrote only stuff geared for an adult audience. You know, Beasts Made of Night, Crown of Thunder, War Girls, all of that was sort of a happy accident. I almost fell into YA. So Riot Baby very much felt like a homecoming. And it’s interesting—one of the most fascinating things that has happened with regards to talking to people about Riot Baby in interviews and what have you is they’ll constantly bring up the word “dystopia.” And there’s a part towards the end of the book that gets into the near-future, but the vast majority of it is set in the here and now, in the recent past, but they’ll still use that term “dystopian.” And it got me thinking, dystopian for whom? Because this is just stuff that I’ve seen. This is stuff that I know people have experienced and that I’ve witnessed and that I’ve heard, that I’ve watched people suffer through. What happened after Rodney King, is that dystopian? You know, dystopian for whom? And so that I think is a very interesting new dimension to what I’m having to consider with regards to the fiction that I’m writing that wasn’t necessarily like—you know, War Girls is set like hundreds of years into the future, so you could see it with that: “dystopian.” It doesn’t really work with Beasts or Crown, but it’s interesting seeing dystopian applied to aspects of the African-American experience.

MJ: I thought of that as well, because I was reading it—the first time I read it, I read it with that in mind, and I was almost searching for the dystopian elements, because a lot of it’s like, What are you talking about? This shit is going on now. And I remember where I was when the Rodney King riot happened, the LA riots. I’m not even sure if we should be calling it riots. I’m curious about when did you realize this is a story that had to be told? Because usually with books, the good ones, you feel like this is a story that was waiting to be told. When did you realize that?

Buy the Book

Riot Baby

TO: Probably some time in 2015.

MJ: [deadpan] What the hell was going on in 2015?

TO: [laughs] So this was around the time that there was this flood of videographic evidence of police-involved shootings. So you had the security footage of Tamir Rice’s shooting, you had the dash-cam footage of Laquan McDonald, you had the footage of—oh my goodness, I’m blanking on his name, but the gentleman in North Charleston, South Carolina, who was shot while running away from cops—you had all this videographic evidence. Even Philando Castile’s final moments, which were broadcast on Facebook Live. And after so many of these instances of police-involved shootings, it was the same result: the perpetrator suffered no consequences. It got to the point where we were just asking for an indictment. Just, like, give us anything. Or like, at least give us a trial. Like, something. And we couldn’t even get that. So I was, by the end of 2015, I was in a very angry place. And I was working actually for the Civil Rights Bureau of the Office of the Attorney General. And I graduated from law school earlier in the year, and so I was ostensibly working in a position that was meant to enforce the civil rights protections for the people of the state of New York. And yet all this stuff was happening. I felt this immense powerlessness. And this story was a way out of that. And it’s interesting too, because there was one point I was like, Oh, am I writing this to, like, try to humanize black people in the eyes of a white audience? And I was like, No. I’m literally writing this because if I don’t get this out of me, something bad is going to happen to me. So it was very much driven by this impetus of catharsis. I just needed to get it out of me. And then, I was working on it, and then after we sold, and I was working with Ruoxi [Chen, the Tor.com Publishing acquiring editor for Riot Baby] on it, and we made the connection to South Central, and to Rodney King and all that, I was like, Wait a second, it’s a thing! It’s a thing that can become this incredible statement about a lot of what’s going on in Black America, and a lot of what has been going on.

MJ: Even if we go back and forth with the term “dystopian,” there are elements of speculative, elements of sci-fi, even elements of, say, super-hero […] and I wondered, was that a response—I almost felt as if Ella’s powers came about almost in necessity, as a response to—and of course, at the end, homegirl responds in a major way. But if that’s why, let’s call it the superpower element, showed up.

TO: So I spent a lot of time thinking about what I wanted the manifestation of her powers to be, because she does essentially grow into what you could call god-like capabilities. But I don’t necessarily want to have a personality-less Dr. Manhattan-type character.

MJ: Yeah, we don’t want a female Dr. Manhattan. Because they’re going to get one next season on Watchmen.

TO: We could talk about that later! I wanted her to have powers that responded to the story and responded to instances, specific instances in the story, and responded to scenes, as a sort of narrative device, really. Like, I wanted her to have powers that would allow her to show Kev what she was trying to show him and to try to bring him along on her mission. Also, too, I wanted her powers to be something that she’s struggled with, something that she’s tried to figure out how to control, and that control being something that say, for instance, her mom or a pastor is trying to get her to get a hold on her anger because she thinks that she’s angry, then these powers will hurt people or what not. But at the end of the day, a lot of this was just me saying Magneto was right. [audience laughs] You read House of M, right?

MJ: House of X, and Powers of X.

TO: House of X, yeah. So when Magneto turns around and he’s like, You have new gods now, yo! Fam. Faaaaaam.

MJ: I just really like the premise of Powers of X. Like, You know what? Humans are shit. And they’re never going to change, so let’s stop. Let’s just stop.

TO: Yeah! No, but I think it’s really powerful to see that statement made, because I think with a lot of, you know, ‘race talk’ in America, particularly when it zooms in on interpersonal relations, and like, the individual and whatnot, you know, it’s the Rodney King thing, like Why can’t we just get along? and whatnot. But like, it’s sort of like with climate change, right, Oh, stop using single-use straws and whatnot when really, there’s like 43 dudes on the planet who are responsible for like 83 percent of global carbon emissions. And if we just went after them, we’d do a lot more in terms of stemming the tide of the apocalypse than compostable sporks.

MJ: Rather than telling quadriplegic people, No, don’t eat.

TO: Yeah, no, exactly! And so I feel like it’s a similar thing that I was trying to get at with Riot Baby, where so much of the dialog was along the lines of individuals and interpersonal relationships and, like, trying to change the mind of a single reader, or what have you, and I was like, No, it’s systems, you know? It’s systems.

MJ: Yeah, and you get the sense in this novel—not “get a sense,” it is there—that the real, overriding villain is structural racism.

TO: Absolutely.

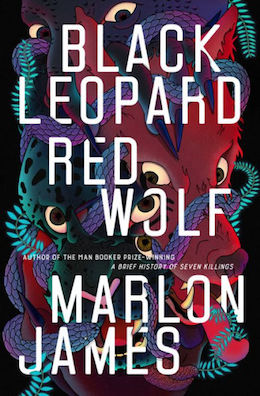

Buy the Book

Black Leopard, Red Wolf

MJ: And structural racism’s distant cousin, who I love that you mention, appears when Ella says, “When there isn’t a curfew. Pastor, this isn’t peace. This is order.” And I was like, Damn, MLK’s Letter from Birmingham Jail—

TO: Absolutely.

MJ:—where you think they’re allies, but they’re far more, basically, My desire for freedom and equality can out-trump your desire for order.

TO: Absolutely. There was this essay in the New York Review of Books that Namwali Serpell, this incredible Zambian author, had written, and she was referencing an anecdote from either a German or a Polish woman who had lived near the gas chambers during WWII, and how she had complained to I think it was an officer, a German officer, if they could, like, get rid of them. Not because she was offended by what was happening to the Jews in there, but because she just didn’t want to have to deal, you know, aesthetically, with all that stuff that was going on. And so oftentimes, when I overhear or participate in discussions on race myself, you get from the other party a sense of annoyance, right? It’s like, they don’t want the problem to go away because they care about the person affected. They want the problem to go away because it’s spoiling their lunch. You know? It’s that sort of thing. And so who’s status quo are we talking about? If there’s no violence, there’s still some hierarchy going on. That means there’s always going to be somebody on the bottom, and is that a sustainable position to be in?

MJ: The reason why it echoed for me is because of what the novel is and when it’s set, and we’re talking about the Rodney King protests and so on. The civil rights ally, the whatever ally, always distances when it turns to riots. Because again, they’re concerned with order over rights or concerns for justice.

TO: Absolutely. We see it every time there’s any sort of protest movement and people start to come out of the woodwork to police it, right? Like, Oh, don’t block the freeway, like, Oh, that’s too disruptive. Or like, Oh, don’t kneel, that’s too disrespectful. Like, come on! Come on! Really? And so it’s like every single time—

MJ: Yeah, we should protest at 4 in the morning, when there’s no traffic—

TO: Exactly! Just protest when it’s convenient for me.

MJ: And sing something so I can go, I was touched.

TO: [laughs] No, you’ve got to have Sarah McLachlan playing in the background, that’s what you—

MJ: You know what? I happen to like Sarah McLachlan. Anyway, so the characters literally move. But they also feel literally hemmed in. And I mean, if there is ever a metaphor for the black experience, there it is. How much of that contradiction do you think powers the novel? And the second part of that question is, is that also—because some parts of this novel, for something called “dystopian,” ties into a lot more narratives, like the “flying Negro.” Ella spends so much of this novel traveling, literally in flight, but everyone’s also so trapped and confined.

TO: Yeah, that sense of claustrophobia was absolutely intentional. In each chapter, there’s a very specific location that the chapter is set in, and I wanted to physically deviate from that place as little as possible, because I wanted to give the reader that sense of claustrophobia and of being trapped. And when you’re trapped, it’s not as though you’re completely, like, bound, and can’t like move your arms or your feet. You can walk around the confines of your cell. Like, you can still move, but it’s still a cell. And so I wanted to look at different ways in which that would manifest. In some places, your cell is the corner outside the bodega. Like, that’s really where you live your life. In some places, your cell is the halfway house that you live in after you get put on parole. But it’s all a cell. You can’t leave that place or can’t really live a meaningful life outside of that place. And so that was absolutely intentional, trying to maintain that claustrophobia, but also trying to show how universal that feeling is across the country. It’s not just a LA thing, it’s not just New York thing, it’s felt all over the country.

MJ: And for Kev, flight is almost always a mental thing.

TO: Mm-hmm. Absolutely.

MJ: It’s travel, but you’re still bound. Let’s talk about whiteness.

TO: [chuckles]

MJ: I pause for dramatic effect. [Audience laughs.] Because we talk a lot about—not here, but you hear a lot of talk about the white gaze and so on, but Ella spends a lot of time literally gazing at whiteness.

TO: Yeah, that was—oh man, that scene at the horse race was so much fun to write, because you could… So you could feel her disdain, right? And it’s like she’s completely invisible. And that’s the reality of so many people of color in the country and in the world and in this present-day reality. And she’s able to sort of literalize that and express through her superpower this just, like, dripping Look at you all. It was the feeling I got when whenever I would see a picture of—what’s his name? The guy that used to be 45’s advisor, Steve Bannon!—whenever I would see a picture of Steve Bannon on TV, this dude looked like a bag of Lay’s potato chips that had opened and left out in the sun for two days. [MJ: Yeah] And I’d be like, wait, you’re supposed to be the master race? Like [skeptical face]. [MJ laughing.] My guy. My guy. But being able to have a character express, being able to have a character look and gaze at white people, and just really, really not like them, I think that was a very interesting thing to delve into, because I don’t know that I’d seen that, or that I’d seen it from a position of power. This woman who’s walking among them could literally obliterate every single one of these people that she’s looking at, and it’s almost like she’s descending from the clouds and she’s just like walking amongst the subjects and just like, ugh.

MJ: But what is she learning?

TO: I think she’s reinforcing that perspective that she has, that What’s coming to you all, I feel no qualms about it. Because she’s, at that point in the book, not completely all the way there yet. But she does these walks to convince herself. And also like, during the context of this, her brother’s locked up in Rikers, right? So the person that she loves the most in her life is in this hellish environment. She’s watching all these white people walking around free and seeing what they do with their freedom, what they’ve done with their freedom, as a way of sort of convincing herself, Okay, when it gets time to go to the mattresses and do what I gotta do, you know, ain’t no half-stepping. And I think that’s what she’s telling herself in those moments.

MJ: In a lot of ways, it feels like Ella is the Riot Baby.

TO: Yeah, so the earliest incarnation of this story didn’t have the South Central chapter. So it started with Harlem and then it went to Rikers and then Watts. And the focus was much more on Kev, and the story was more about the ways in which technology and policing in the carceral state would intertwine to give us a picture of what that might look like in the future. Algorithmic policing and courts using risk-assessments to determine when you can go on parole or at any stage in the proceedings when you could get your freedom, drones, the use of military tech domestically, with regards to policing. But then I started having conversations with my genius editor Ruoxi, who I’m going to shout-out right over there [pointing out Ruoxi in audience] in the striped sweater: galaxy brain. Absolute galaxy brain. She very simply prodded me in a different direction. She was like, Well, what about Ella? Like, I’m not necessarily getting enough Ella here. Where does Ella come from? What’s her arc? Because before, it was very much about Kev and Ella sort of paying witness to what he was going through and not being able to protect him. But then, I started thinking, Well, what about Ella? Where did they come from? What was Ella’s story? What was Ella’s life like before Kev came along? And then, I started thinking about how old these characters were. And I was like, Wait a second, shit, they’d be alive for Rodney King! And even if they weren’t there for Rodney King, they would have seen Rodney King on TV. Because I just remember, being a kid, before I would go to school, I would see footage of the beating on like, The Today Show in the mornings before going to school. Which is like wild! I was like, y’all showed that on a morning show before kids went to school?

MJ: How old were you?

TO: I must have been like 8.

MJ: Wow, I was on to my 3rd job. But go on…

TO: [laughs] I mean, I was 8 in a Nigerian household so I was also on my third job.

MJ: [laughs]

TO: But that opened up so many new story possibilities, so many new opportunities to really deepen thematically what was going on in the story. So I was like, Wait a second, they’re there! They’re in South Central. They’re in LA for that. That’s their first riot. And then you have these flash-points throughout the book. It’s interesting. Kevin’s the one that’s born during the actual riot, but I think it is a lot like you say, where Ella is the one that embodies a lot of what I see when I look at that particular kind of conflagration.

MJ: It’s kind of a baptism for her.

TO: [nodding] yeah.

MJ: People who were inevitably attacking this book would say it was a radicalization.

TO: [laughing]

MJ: [sarcastically] Because you know you black people are all terrorists.

TO: Oh yeah, no, absolutely. It’s like, there’s always the joke about, you know, if you want gun control law, then start arming black people.

MJ: Because it’s worked twice before.

TO: [laughs] Yeah—

MJ: I’m not even kidding. In history, the two times gun control happened was because of that.

TO: Yeah.

MJ: I was like, yeah just send somebody down any Main street, you got gun control in ten minutes.

TO: My thing is, if they see this as radicalizing, I’ll just show them House of X. Or I’ll show them anything with Magneto in it. That’s your guy! That’s the guy right there. How is this any different than that?

MJ: Well, I’m sure some people who have issues with House of X are like, Hold on, you’re saying Magneto was right all along?

TO: Yo, like, that was the thing! Alright, sorry, I’m going to get really excited for a second. [MJ laughing] So my introduction to the X-Men was through the animated series. And I remember it’s like the second or third episode where— In the previous episode, the X-Men tried to raid a sentinel facility, everything goes sideways, Beast gets captured, and in the following episode, at the very beginning of the episode, Magneto comes and he tries to break Beast out of jail. And he punches this huge hole in the wall and he’s like, Look, Beast, we gotta dip, and then Beast is like No, I’m going to submit myself to the human’s justice system, and they have this whole like, really explicit discussion about separatism vs. integration. Like, on a Saturday morning cartoon. They don’t disguise it or anything. But I distinctly remember even as a kid really glomming onto Magneto’s perspective, because I think even at that age, I’d seen that it was almost impossible— Even at that age, knowing the little bit of American history that I knew, it seemed almost impossible that you would get a critical mass of oppressors to change. And they would do it out of the willingness of their heart? Whenever I would come across like, Magneto was right, or an expression of that in those books, I was like, No, but actually. And so when House of X came along, Powers of X, it was almost a literalization of that. And I felt so vindicated, but yeah. So I’m a bit of a Magneto stan.

MJ: Speaking of gaze, do you think you write for any gaze?

TO: There are a few Easter eggs in there, but they’re mostly Easter eggs for black people, right? And not necessarily specific references or whatnot, but just like—

MJ: I could see the Jamaican in Marlon. I’m just going to assume that’s based on me.

TO: No, of course not. I know plenty of Jamaican Marlons.

MJ: I actually believe you. One of my best friends is also named Marlon James, so I believe you.

TO: See? There you go. I could have gotten away with it.

MJ: You could’ve.

TO: But even, just like, jokes and the way that we talk sometimes, and—

MJ [to audience]: Also, that’s me proving that I read the whole book.

TO: [laughs] You were faking it this entire time. No, but just like, various jokes and cadences and things of that sort. Or even just like off-hand references. Not just necessarily to other tragedies, but like, rap songs for instance. Like, I don’t say when a particular scene takes place, but I say that there’s a car that’s blasting Dipset Anthem on the radio as it’s rolling by, so if you were alive in 2003, you know exactly where and when that scene’s taking place. It’s that sort of thing. I wrote for myself. I was going to say I wrote for us, but I don’t necessarily— Like, “us” is such a big thing? The multiplicity of blackness is infinite, right? But it’s like, me and my people. I wrote for me and my people.

MJ: Do you get the sense that Kev’s life could have turned out any other way than it did?

TO: I mean, if he were lighter-skinned, maybe, but I really— So, when I was in film school, like, just down the street, and I was really poor and broke and I would occasionally for, like, spiritual rejuvenation, wander the stacks of The Strand, and this became like a second home to me, and even when I couldn’t afford to buy anything, it was still good to be here, so thank you Strand for having me. But when I was in film school, we studied a lot of plays and a lot of sort of Greek tragedy. And one of the things I really really latched on to was this idea of prophecy. Or like the inevitability of things. Reading Oedipus Rex, you see him constantly trying to fight against the things he knows is going to happen. Or anytime there’s a really well-pulled-off time-travel narrative. And you spend so much time trying to figure out how they’re going to get out of it, how they’re going to change their course, and you see them doing all these things, all these things that make it in your mind impossible for this out-come to actually happen that’s already predetermined, but somehow it’s still happening. And so I really appreciated that element that’s very pervasive in a lot of Greek Tragedy, and I see so much of it in the black experience in America, particularly the more tragic sort of aspects and elements of it. There is this, almost this feeling of inevitability, and that I think is one thing that I wanted to have fuel Ella’s sense of hopelessness, and certainly the hopelessness that I felt when I started writing this book. Because it seemed like this was constantly happening. Constantly constantly constantly happening. And it was almost as though there was this mockery being made, because I know in the past, when you would talk to people about police brutality, they’d always, like, want either out loud or in their head, evidence, right? There was always talk of, like, oh, you don’t know the cop’s side and you know, where’s the dash-cam footage, where’s the evidence? Et cetera, et cetera, et cetera. And then, it got to the point where we had all these instances of evidence, of videographic evidence, of unequivocal, like this is what happened here. And over and over and over, there would be this sort of reiteration of injustice. And for me, it’s very difficult to look at that. Particularly in the year 2015 or the year 2020, after everything that’s happened, and after all the record-keeping we’ve done as a society, like all the tweets all the receipts, all of that, right? To see that and know that the outcome is still going to be the same, it’s almost like— It’s Aeschylean. That to me is part of the height of drama and tragedy right there. It’s that inevitability. So I think that inevitability is very much Kev’s life. Like, that’s his destiny. You see it when Ella’s looking at other people and she sees their futures. It’s not as though she sees alternate futures. She sees what’s going to happen to then.

MJ: Does this mean you’re fatalistic?

TO: [breathes out heavily, then laughs] Well, it’s interesting because I have a very weird and interesting relationship with faith and with religious faith.

MJ: Faith or fate?

TO: Actually, both. Now that I think about it. I’m the oldest of four, and my dad passed away when I was 10 years old, and it’s been my mom raising the four of us ever since. And she’s very religious. We grew up in a very religiously robust household. I got picture book versions of the bible read to me ever since I was a young warthog. But one thing that was really interesting to see was to watch her aftermath in my father’s passing, after everything that she’s had to endure and go through and everything, just cling to her faith. And it didn’t even, at least from my perspective, what was less important was what she believed in, what was more important was how fervently she believed. And how she felt that belief carried her through the roughest part of her entire life, and enabling her to endure that but also to take care of these four kids and put them in like the best schools in the country and all of that. So that was really powerful to me as a kid and even growing up and going through college. At the same time, I think with regards to fate, I think— I have a very fatalistic view of individual change. There’s this idea that books are empathy machines. And the way that I look at it is that if you’re walking by a lake and you see a kid that’s drowning, you don’t have to know physically what it’s like to drown to feel the urgency to jump in and save that kid. You feel this sort of moral empathy, like Let me go save this child. When you’re reading a book, and you’re cognitively living in the space of the characters, you may not necessarily feel the type of moral empathy that gets you like out in the streets afterwards. But you have this cognitive empathy. So there are like these two dimensions of empathy and it’s the type of thing where it’s not beyond the pale of imagination for me to see somebody on the sidewalk reading this book (although it would be really cool if I saw anyone on the sidewalk reading this book), and walking down St. Nicholas and you know get to that corner of St. Nicholas and 145th St, see a bunch of dudes like Kev and his homies hanging out there, and cross the street while reading this book. Those are the two different types of empathy at work, and so I just like— If you want somebody to change with regards to an issue of social justice, you have to force them to. If somebody’s in power, why would you just give that up out of the goodness of your heart?

MJ: Yeah, I mean, it sounds like— We get to questions— Because it’s always been my sort of pet peeve, empathy, which I actually don’t believe in.

TO: Interesting. Just like, at all?

MJ: I think empathy as a force of change is a very silly idea. [Looks to crowd.] It got so quiet.

TO: It just means that it complicates—

MJ: Yeah!

TO:—it complicates the discussion of why people write books.

MJ: Did you say “why people” or “white people”?

TO: [laughs, with crowd] I mean, we know why white people write books.

MJ: I mean, if we’re going to talk about American Dirt now?

TO: Shoe-horning it in because—

MJ: We have a Q&A coming up!

TO: [Laughing]

MJ: Okay, we’ll both have one statement each on American Dirt.

TO: Mine’s gonna be a long statement.

MJ: Somebody asked me the whole thing about writing the Other. How do you write the other? Two things: One, you need to let go of that word, “other.” And two, I said, You know what? Just put this in your head. What would Boo do? Go read Katherine Boo’s Behind the Beautiful Forevers—

TO: So good!

MJ: —Read it again. Read it a third time. Then dash away any shit you just wrote, and be like her. And I was like— Because like— I can’t have this— I’m so tired of this thing. Like, I’ll ask people Well, how come the crime writers don’t fuck it up?

TO: Nobody’s coming for George Pelecanos or Richard Price or Dennis Lehane and they’re writing all these characters of color. But they’re doing it right!

MJ: Yeah, because they do research. Something Katherine Boo also said, and I’m sure I’m misquoting it, something about almost getting it right overrides getting it emotionally or with emotion so on. And usually the thing that Boo and Price and Pelecanos and Márquez all have in common is that they’re all journalists. Which is why, in my— Usually, if people are going to be doing creative writing in my class, I force them to do a journalism class. Anyway, what were you going to say?

TO: I mean, I’ll—

MJ: We have some questions; this can’t be 30 minutes.

TO: This will be like a multi-part statement. I’ll preface this by saying, Look, if you paid me a million dollars, feel free to drag me to hell. [crowd laughs] All over Twitter, [MJ laughing] say whatever, like, if I ever got paid a million dollars for anything that I wrote, I—

MJ: I got a mortgage, damn it.

TO: I got student loans! Like, what do you want from me? No, but I think it’s one of those very fascinating things where personally, not being Latinx or Chicanx myself, it was one of those instances where I had to force myself to sort of pay witness to what was going on. And really think about what I was observing. And I know, because I’d been seeing the book cover everywhere in the months leading up. And it was always being publicized. I didn’t necessarily know what it was about at first, then as we got closer, it was like, Oh, this is like a migrant novel. And then it started coming out, or at least over MLK weekend, I started seeing the big like blow-up on Twitter. And I saw all the people that were praising it happened to be uh, I guess the word is monochromatic?

MJ: Mm-hmm. [crowd chuckles]

TO: And all the people that were castigating the book and a lot of the publishing apparatus that surrounded and supported the book happened to be people of color, largely Chicanx writers. And it was one of those things where I was like, Okay, like these people have actual skin in the game. Like, why are they not being listened to the way that the folks lauding this book in review publications are being listened to? And it’s almost like every single day when you think the whole thing can’t get worse, it like gets worse. There’s some other aspect of it that’s revealed—

MJ: It’s like wow—

TO: —And it’s not— I’m not saying Oh if you’re white you can’t write any other ethnicity or like whatever, you can’t write outside your experience. No, it’s just like Do it right. Like, don’t italicize every single Spanish word. Like, why would you italicize Spanish in the year of our Lord 2020? Come on!

MJ: I went to her [does air-quotes] “abuela.”

[TO and audience laughing]

***

You can watch the full talk, including the audience Q&A session, below.